‘Being Greek’ more related to adopting customs and a way of life than having Greek parentage

Effrosyni Charitopoulou

Previously, Angelo Tramountanis has explained why young Greeks may be challenging some well-established attitudes towards Greek identity. In this article, Effrosyni Charitopoulou demonstrates that the Greek population as a whole may be opening up to new understandings of “Greekness”.

Until the 1990s Greece was mainly a country of emigration, and for a long time Greek society was characterized by a high degree of ethnic homogeneity. However, with the arrival of immigrants from Eastern and Central Europe at the end of the 20thcentury, this pattern gradually changed, and Greece transformed into a country of immigration.[1]By implication, the social background of Greek residents became comparatively to earlier decades more diverse.

Despite this, until recently Greece’s citizenship regime reflected the patterns of emigration. Greek nationality could be acquired primarily on a jus sanguinis basis: it could be passed to people mainly through their parents. Naturalization was extremely rare, as the requirements were rather restrictive. This made it almost impossible for second-generation migrants, who were either born and raised or raised in Greece, and whose numbers have thus grown, to acquire Greek citizenship. However, in July 2015, the 4332/2015 Law, backed by the ruling SYRIZA party and the PASOK and Potami parties, was introduced. This Law relaxed the highly restrictive citizenship regime and thus offered a legal pathway for second-generation migrants to acquire Greek citizenship.[2]The main prerequisite for naturalization is participation in the Greek educational system.[3]Official statistics suggest that in the period up until mid-2018, approximately 80,000 children of migrant descent acquired Greek citizenship on this basis.[4]

Against this background, how do Greeks define “Greekness” today? Do they still consider that the right to Greek citizenship should be determined on the basis of parental ethnicity, or do they consider other characteristics essential? Data from the Voices on Values survey suggests that Greeks associate “Greekness” with the adoption of customs and way of life, while a blood-based understanding of it, although still common, is not considered the most important dimension to be seen “Greek”.[5]

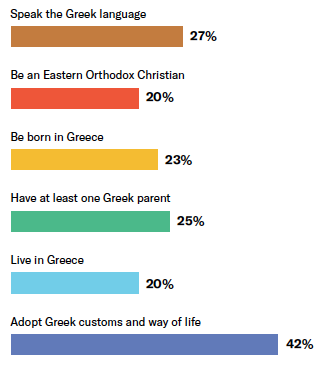

Specifically, as shown in Figure 1, 42% of Greeks believe that the adoption of Greek customs and way of life is essential for someone to be considered Greek, while 27% say that an ability to speak Greek is also essential. In other words, the characteristics Greeks most commonly define as essential to “being Greek” are acquired rather than innate.

Figure 1: Perceived essential characteristics for a person to be seen as Greek

At the same time, an important minority also considers that “Greekness” is intertwined with blood-based characteristics: 25% of respondents highlight that Greeks should have at least one Greek parent, a view in line with the previous jus saguinis Greek citizenship regime. The places of one’s birth and residency are essential to defining someone as Greek for 23% and 20% of Greeks respectively, reflecting a jus soli understanding of “Greekness.” Surprisingly, belonging to the Eastern Orthodox Christian religious denomination is considered an essential prerequisite for someone to be seen as Greek by only 20% of Greeks. Given the Greek Orthodox religion is a central component of national identity[6]one would have expected a larger percentage of Greeks to consider this characteristic as essential to “being Greek.”

Drawing on evidence from the Voices of Values survey, it seems that Greek public opinion is somewhat in line with the wider definition introduced by the new citizenship regime. More Greeks associate “Greekness” with a way of life than with “blood” or “soil.” Ultimately, this more inclusive understanding of “Greekness” means that second-generation immigrants are able to share the most “essential characteristics of being Greek.”

Effrosyni is currently pursuing a doctoral degree in Sociology at the University of Oxford. She holds an MSc in Sociology from the University of Oxford and an MA in Economics and International Relations from the University of St Andrews. Her research interests lie in the field of political sociology and specifically on issues surrounding prosocial behaviour, attitudes towards migration and far-right voting. She has served as an A. S. Onassis scholar.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

[1]Triandafyllidou A. & M. Veikou. (2002), “The hierarchy of Greekness: Ethnic and national identity considerations in Greek immigration policy,” Ethnicities 2(2): 189–208.

[2]Note that a similar law had passed in 2010, but was short-lived. For a discussion, see: Christopoulos D. (2017). “An unexpected reform in the maelstrom of the crisis: Greek nationality in the times of the memoranda (2010–2015),” Citizenship Studies 21(4): 483–494.

[3]Note that if the person was born in Greece, fewer years of Greek schooling are required to apply for Greek citizenship.

[4]See https://www.hellenicparliament.gr/UserFiles/67715b2c-ec81-4f0c-ad6a-476a34d732bd/10722178.pdf, last accessed 14.11.2019 (in Greek)

[5]The Voices on Values survey presented Greek respondents with a number of characteristics, asking them to say which they consider necessary for a person to be seen as Greek.

[6]Chrysoloras, N., 2004. “Why Orthodoxy? Religion and Nationalism in Greek Political Culture,”Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 4(1): 40–61.