Political representation and the AfD: Intolerably intolerant?

By Magali Mohr.

Should open societies integrate the positions of those who seek to go against its core principles and values? Using data from our Voices on Values survey, we focused on the right to political representation, and found that drawing the boundaries of an open society is a delicate balancing act.

Karl Popper said it all in 1945 when he wrote of the “paradox of tolerance”.

“Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them.”

Now that right-wing parties and movements are on the rise across Europe, the question of whether and how an open society should respond is again topical.

In Germany, almost a year has passed since the xenophobic AfD party, with some of its members openly denying the Holocaust and branding it a myth, entered the Bundestag.

As the first far right-wing party to obtain enough votes to enter parliament since the German Party (Deutsche Partei) in the 1960s, its arrival in the Bundestag was seen as a “historical set back, (…) a test for German democracy”, if not an “attack on democracy”. The question of “How much AfD can democracy tolerate?” was often asked.

But representative democracy and the right to run for political office are fundamental principles of German law. Ralf Dahrendorf, one of the most renowned German liberal intellectuals of the past century, said “liberal democracy is government by conflict”.

So how should the public outcry over the AfD’s election be judged? How do Germans balance the right to political representation with their support for democratic principles? In short, what do they think of the AfD’s presence in parliament?

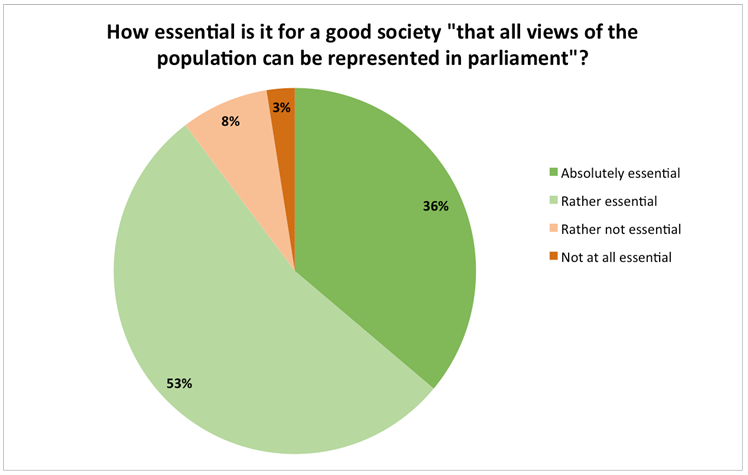

Figure 1: The importance of political representation

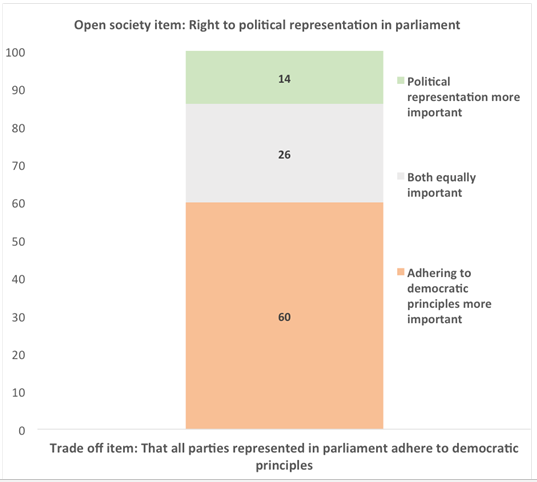

Asked about the importance for a good society of parliamentary representation, 89 percent said it was essential. A third had said absolutely essential (Figure 1). Yet when asked whether adherence to democratic principles was even more important, 60 percent said yes (Figure 2). A quarter of respondents considered the right to political representation to be equally important, and a small minority of 14 percent thought that right more important than democratic principles.

Figure 2: Trade-off political representation vs adherence to democratic principles

These findings are particularly interesting because German electoral law stipulates that to enter the Bundestag political parties must either win at least five percent of votes or have three directly elected seats. Introduced in 1953, this threshold was intended to avoid the fragmentation of post-war Germany’s new parliament. Every party entering the Bundestag must therefore have enough popular backing to show it is relevant to a substantial segment of society.

Yet almost two-thirds of the Situation Room’s German respondents nevertheless consider adherence to democratic principles as being « more essential » than the right to political representation. The fact that the AfD entered the Bundestag means that the five percent threshold clearly doesn’t provide enough protection to ensure that all parties in parliament have liberal democratic views.

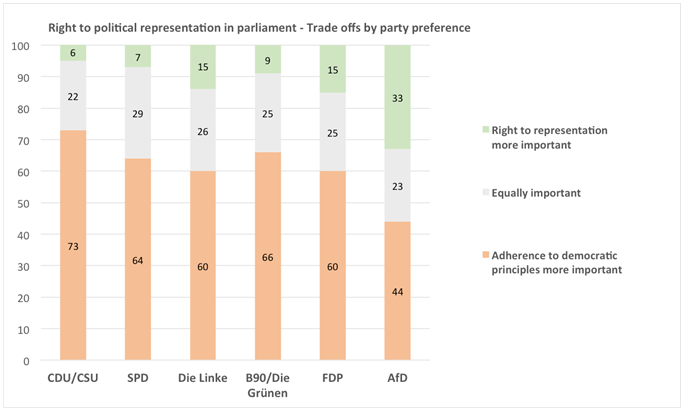

So, in wanting to protect democracy, those opposed to the AfD are willing to discard political representation in favour of adherence to democratic principles. Whereas AfD voters, who probably know that some of their party’s views are considered undemocratic, are at least twice as likely as people affiliated with other parties to be in favour of the right to political representation (Figure 3). Open society principles, as in this instance, may have unexpected supporters, which demonstrates the need for subtlety in understanding the motivations behind some political choices.

Figure 3: Trade-off by party preferences

This tells us two things: First, that a simplistic understanding of open society “advocates” and “enemies” is misleading. Regarding the AfD, this means that we need a more nuanced understanding of AfD voters’ motivations. Second, that protecting open society values and liberal democracy is an increasingly delicate balancing act.

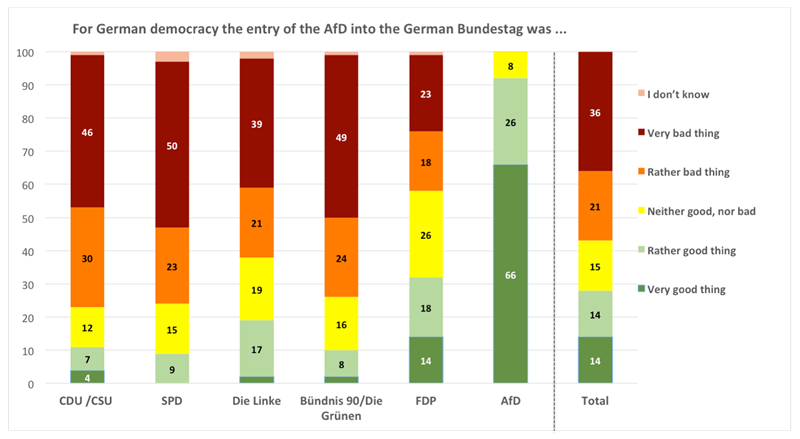

Then how do Germans assess the right to political representation when the AfD is concerned? Overall, 57 percent considered AfD’s presence in parliament as “very bad” or “rather bad” for democracy, but there were cross-party variations (Figure 4). Apart from AfD supporters themselves, voters for the leftists Die Linke and liberal FDP were the least likely to see this as a bad thing.

Figure 4: Evaluations of AfD’s entry into the Bundestag

The Free Democrats (FDP), the party of liberal intellectual Dahrendorf, has traditionally advocated parliamentary conflict. But that doesn’t explain why 19 percent of Die Linke’s voters thought that the AfD’s presence in parliament was good for democracy?

One possible explanation, applicable both to the FDP and to Die Linke, may be their opposition to Angela Merkel’s fourth term as chancellor. There is increasing frustration, especially among opposition parties, with her consensual style of leadership. Rather than an approval of AfD policies, voters’ responses might be seen as hope for a return to lively debate in parliament.

What does all this mean for the open society and Germans’ changing political views? It clearly suggests that where we draw the boundaries of an open society is a matter of negotiation. It is a socio-political balancing act, as much as it is a test of voters’ personal interests.

Can this tolerance paradox be resolved? Popper said we should claim “in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant”. But where does intolerance begin? Must we accept the verbal stigmatisation of refugees, as practised by the AfD? The erecting of crucifixes in public institutions while prohibiting other religions’ symbols by the federal government in Bavaria? Are we ourselves not becoming intolerant by not tolerating the intolerant? Perhaps we must accept that open society values can sometimes clash, and that we must trust the ability of an open society to live with this kind of conflict.

–

Magali Mohr is a Research Fellow at d|part.

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.