The Brexiteer: Not a black box

By Jan Eichhorn.

It is easy and popular to blame certain groups of the population for decisions that challenge our open societies. Particularly often singled out are the socially disadvantaged. Whether populist leaders get elected or referenda are won by people with nationalist orientations, commentators (who often form part of a civic, media, or political elite) are quick to explain it as a form of resistance by the losers of globalisation. However, looking at the available research data we quickly see that we should be very cautious with conclusions and typologies as there are a set of factors at play when it comes to people’s political choices.

One of the most poignant current cases illustrating this issue is the discussion that has followed the referendum vote of the United Kingdom to leave the European Union. Many newspapers have linked the Brexit decision to people characterised as the “losers of globalisation” who supposedly saw the referendum as their opportunity to rebel. This narrative is present in different political orientations and media outlets, ranging from the Financial Times to the Guardian or the Washington Post. The issue is also linked to class, with The Telegraph, for example, proclaiming that “Middle class liberals were only social group to emphatically back Remain”. These stories leave us with a feeling that the so-called “Brexiteer” is a clearly defined person, who felt they needed to rebel against the status quo because of a (perceived) personal position of disadvantage.

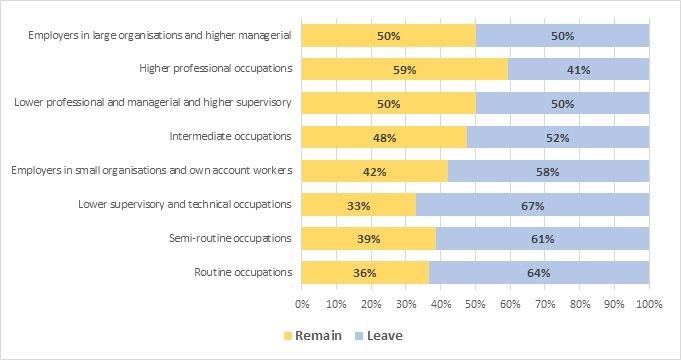

Figure 1: Brexit vote by socio-occupational class (BES 2016) — only voters included

And indeed, we do see differences in support for Brexit based on social position. As figure 1 illustrates (showing data from the British Election Study collected shortly after the referendum), people in lower socio-occupational classes have a greater tendency to support leaving the EU (61 and 64 per cent respectively in the two lowest groups) compared to those in the highest socio-occupational groups (41 to 50 per cent respectively). However, the transition by social class is rather gradual – and not always linear. Higher intermediary middle class categories are split roughly evenly over Brexit, for example. Average differences between the lowest and most other socio-occupational class groups are only about 10 to 14 percentage points (with only one exception: higher professional occupations).

While one’s personal economic position is related to Brexit attitudes, we are far from seeing a country divided into distinct groups of social classes, where the advantaged wholeheartedly embrace the openness of the EU and the disadvantaged reject it outright.

The figures actually paint a very different picture. Nearly half of those in higher middle class positions also support the UK exiting the EU. While percentages are lower than in some other groups, it suggests that divides run deeply through all groups of the population. It appears to be a matter of degree, not type.

Indeed, other researchers have warned about over-simplification and the identification of a singular type of “Brexiteer”, based on social class alone.

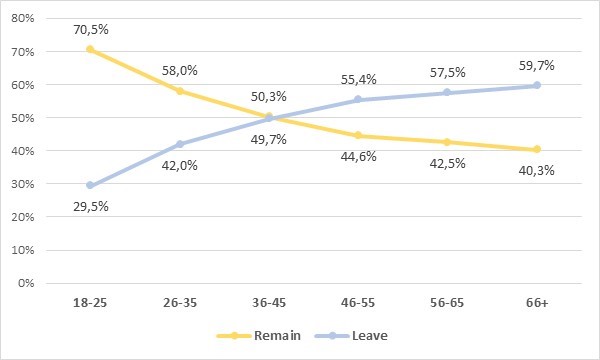

Figure 2: Brexit vote by age (BES 2016) — only voters included

The relationship between age and Brexit attitudes, for example, is much stronger than that of social class (see figure 2) and, importantly, education has been shown to be strongly related to a person’s views about whether the UK should leave or remain. However, even such comparisons do not allow for perfect typologies. Did “the old” as a group cause Brexit? Those aged 66 or above were most likely to vote for it (around 60 per cent), but even amongst them four in ten opposed leaving the EU. And while most young people wanted to remain, around 30 per cent still opted for Brexit.

So caution is most apt. When discussing demographic differences, we should talk about relative differences and tendencies, but avoid painting simplistic pictures that identify singular, homogenous groups for blame, when those groups do not actually exist in such a distinctive form.

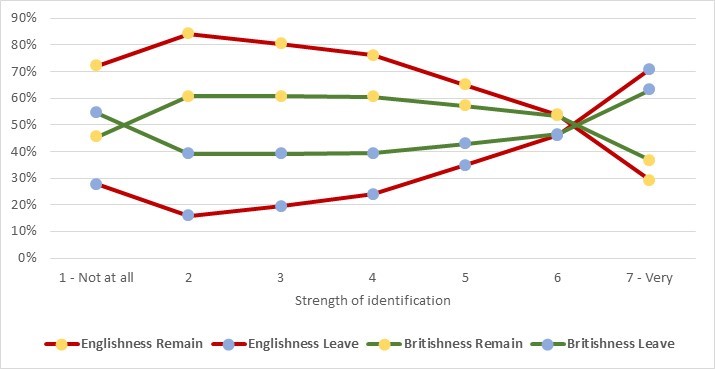

When trying to understand the motivations of people, we also need to go beyond the material, physical characteristics we usually consider when differentiating groups. Otherwise, it would be hard to explain why, for example, also regions in the South of England that are rather wealthy, voted for Brexit — contrary to the often claimed narrative about Brexit being a problem of an apparently poorer North). Questions of identity, for example, matter as well and substantially so, as figure 3 reveals. People in England who feel strongly attached to their English national identity are much more likely to support Brexit than those who do not. Of those who chose the highest value for English identity on a 7‑point scale, over 70 per cent voted to leave the UK. Conversely, over 80 per cent amongst those who only emphasise their Englishness slightly (2 on a 7‑point scale) voted to remain. National identity mattered strongly in this referendum, but is rarely talked about to the same extent as questions of class or even age, although the divide is much more dramatic and cuts across different socio-economic groups in the population.

Figure 3: Identification with Englishness and Britishness by Brexit attitudes (BES 2016) – only voters in England included

But even here, we have to remain careful not to jump to over-simplistic conclusions. Identities are complex and it appears that Britishness, while slightly related to views on Brexit, was much less important in differentiating between groups than English identity was, confirming other research that a particular aspect of the Brexit decision had to do with perceptions of Englishness specifically – which is rarely addressed.

Socio-demographic factors relate to a person’s likelihood of supporting Brexit, but without considering a broader spectrum of attitudinal concerns, such as identity, we will not be able to develop a genuine understanding of Brexit. The considerations presented here should act as a cautionary reminder that we should be vigilant in avoiding the mistake of taking on extensive, typologising narratives about political decisions. We should challenge explanations that misrepresent attitudinal tendencies in some groups of the population as the identification of particular groups that should be blamed as a whole for decisions that we might not be comfortable with and that challenge ideas of open societies. Instead of singling out distinctive groups based on a few demographic characteristics, we should instead try to understand the interplay of the various tangible and intangible factors that may affect the views of people across different groups of the population. Simplistic typologies may create plausible stories, but instead of providing starting points for solutions, they are likely to further the construction of artificial dividing lines that we may bring into existence ourselves. We all, as readers, researchers, and members of societies should there take this on as a task in our daily lives: to challenge those explanations that might just be too comforting and easy to be accurate.

Data reference: Fieldhouse, E., J. Green., G. Evans., H. Schmitt, C. van der Eijk, J. Mellon and C. Prosser (2015) British Election Study Internet Panel Wave 9. DOI: 10.15127/1.293723

–

Dr Jan Eichhorn is the research director of d|part and oversees the work on the Voices on Values project. He also teaches Social Policy at the University of Edinburgh.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.