Why the AfD’s threat to the open society should not be overstated

By Magali Mohr & Luuk Molthof.

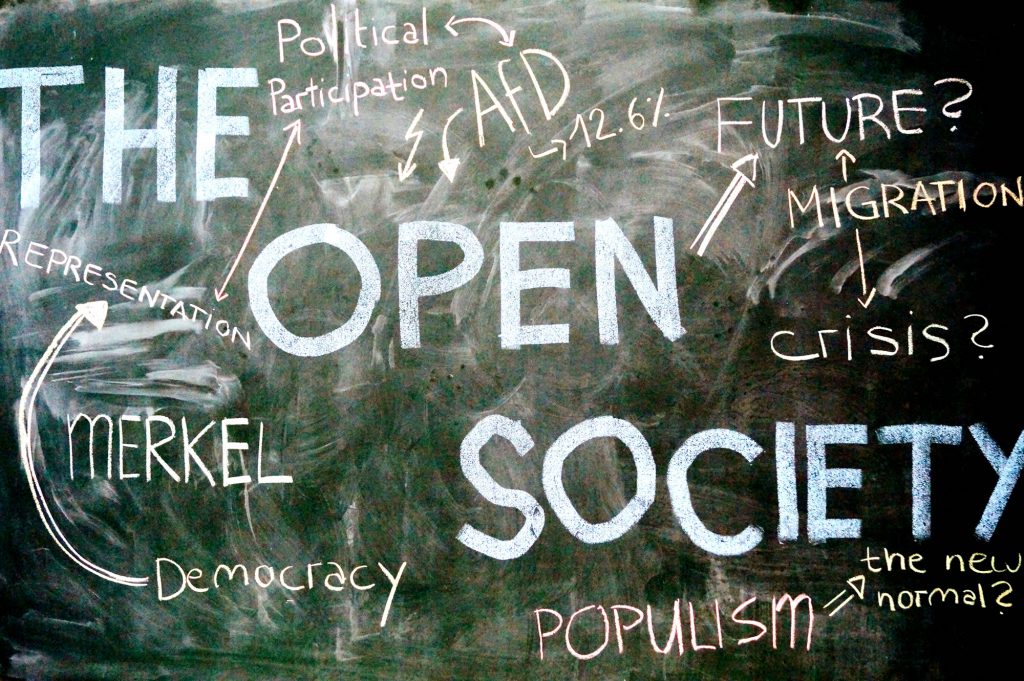

When the coalition talks between the CDU/CSU, the FDP, and the Greens collapsed two weeks ago, there was at least one party that rejoiced at the failure of ‘Jamaica’. The right-wing populist Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), excited about the possibility of a new vote, was hoping to improve last September’s results in a new election. Even if a new vote stays out, the AfD may still benefit from the recent developments. If conversations between the CDU/CSU and the SPD lead to another Grand Coalition, for instance, the AfD would become the main opposition party in the Bundestag, increasing its significance in German politics. Both scenarios – the AfD making electoral gains in a new vote and the AfD becoming the main opposition party in case of another Grand Coalition – are making German politicians and commentators very nervous indeed, leading some to argue for the establishment of a minority government.[1] A similar unease was present last September, when the AfD secured 12,6% of the vote and successfully entered the Bundestag, raising significant concerns among commentators about the potential implications for the open society. However, in this article, we argue that the AfD’s threat to the open society should not be exaggerated. Although the recent rise of the AfD and its entry into the German Bundestag pose new challenges to Germany’s democracy, we argue that, as long as there is an open public discussion and engagement with the AfD and its electorate, Germany’s open society need not be undermined.

Six reasons why the AfD may not pose a threat to Germany’s open society

Christian Social Union (CSU) patriarch Franz Josef Strauß once famously noted that “there must never be a democratically legitimate party right of the CSU”. It seems that, for a long time, the German electorate agreed with him. While in other European countries, populist parties – such as the Dansk Folkeparti (DF) in Denmark, the Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) in the Netherlands, and the Front National (FN) in France – gradually gained ground over the 2000s and 2010s, Germany long appeared resistant to the ‘populist surge’. However, the Pegida-movement, the successes of the AfD in several state elections, and the AfD’s election to the Bundestag have shown that Germany is not immune to right-wing populism.

With its nationalistic and xenophobic rhetoric and standpoints, the AfD rails against certain core principles of the open society, including freedom of religion and cultural pluralism. Its rise in popularity has therefore raised concerns among commentators about the future of the open society in Germany.[2] However, the AfD’s threat to the open society should not be exaggerated. Here are six reasons why.

1) The AfD closes a gap in German political representation

From a European point of view, Germany is rather late to the party. While right-wing populism — in this magnitude — is a relatively new phenomenon in post-war Germany, many of Germany’s neighbours have faced its challenges for more than a decade. The entry of a right-wing populist party into the Bundestag is arguably just the latest step in the gradual ‘normalisation’ process Germany has been undergoing after reunification. Right-wing populism, it appears, is now an inherent — though not necessarily dominant — feature of modern European democracy.

Going a step further, one could claim that far-right political parties are a product of our open societies. A crucial feature of the open society is tolerance for different ways of thinking. This means that even those who oppose core democratic principles should have a right to express and organise themselves. While far-right political parties pose new challenges to our open societies, as long as their grievances are expressed through democratically legitimate means, their participation in the public debate does not necessarily undermine the open society. In this context, the AfD’s entry into the Bundestag could be seen as closing a gap in German political representation.

2) AfD’s success not as impressive as it first seems

Considering that Germany welcomed more than one million refugees since 2015 and experienced several terrorist incidents since then, the AfD’s electoral feat last September may not be as impressive as it first seems. The AfD’s share of the vote (12,6%) still lies below that of many other European populist parties.[3] Moreover, over the last year, the AfD’s support dropped from 16% in September 2016 to 12,6% in September’s elections. This means that the terrorist attack on Breitscheidplatz in Berlin of December 2016 did little to expand the AfD’s base. In other words, while the German elections were dominated by the topic of immigration, the AfD was only partially able to capitalise on this, suggesting that even in an environment prone to anti-immigrant sentiments, a large majority of the German electorate remains committed to cultural and religious pluralism.

3) September election results not a vote against open society principles

Last September, in the context of increased concerns about immigration and security, the large majority of the German public, rather than turning to closed borders, more nationalism, and less Europe, continued to support a tolerant and open society. Of particular note in this regard is Angela Merkel’s win. Although it is increasingly uncertain whether she will be able to serve a fourth term, the fact that she won September’s elections is certainly significant. Merkel’s decision to open Germany’s borders in the summer of 2015 contributed to a widespread perception of Germany as defender of human rights and democratic principles and ultimately lent Merkel her reputation as the “liberal West’s last defender”. Although Merkel’s CDU/CSU Faction booked an 8,6% loss, the fact that Merkel won the elections — and with a significant margin -, despite her controversial decision to invite thousands of refugees, should leave us optimistic.

4) The AfD stimulates the open society debate like no other

The open society and the values pertaining to it developed into a key topic of the election campaign(s) last September – and not least because of the AfD. For all parties, the upholding of the open society became a means to demarcate themselves from the AfD. As a result, the importance of the open society in Germany is — directly or indirectly — repeatedly mentioned in all electoral programmes [4], apart from that of the AfD. Similarly, the open society, what it means, and where it should be headed became topics widely discussed by the public and media. Thus, by railing against certain core principles of the open society, the AfD actually set in motion a public debate about its meaning and value.

5) Potential for politicisation and revived participation

This (unintended) positive effect of the AfD on the stimulation of public debate may likewise hold true for its entry into the Bundestag. A study on the impact of the AfD’s entry into three of Germany’s Landtage found that, while the creation of conflicts and provocation by the AfD can hamper parliamentary processes, their presence may also lead to a politicisation and revitalization of parliaments. Similarly, looking at the AfD’s electorate, the AfD may have a positive impact on voter turnout. Through targeted campaigning and intense use of social media platforms, the AfD was able to mobilise 1.2 million non-voters in their favour. Although this success is also indicative of the failings of mainstream parties to reach out to voters beyond their traditional electorate base, in terms of political participation — a core pillar of the open society — positive development is apparent.

6) Integrative potential of parliamentarism

Just as the AfD’s entry into the Bundestag is likely to affect the parliamentary process, so too is it likely to affect the AfD itself. Through bureaucratic processes and an increased understanding of the workings of politics, even radical parties typically slowly become part of the “establishment”. Here the evolution of the German Green party over the past 30 years is telling. Having emerged in the 1980s as left-wing, anti-capitalist and anti-bourgeois movement, strongly opposed to armaments and critical of the system, the Greens now call for strong police forces. This socialisation effect of parliamentarian experience may well, if only gradually, likewise have an impact on the AfD’s orientation and its outlook on the democratic process.

Safeguarding the open society requires engagement

It is difficult to predict, at this point, whether the AfD will be able to capitalise on the current coalition chaos. However, independent of the developments over the next weeks and months, the AfD looks like it is here to stay. In this blog we argued that while this new reality poses challenges to Germany’s democracy, the AfD’s threat to the open society in Germany should not be overstated. As long as there is an open public discussion and engagement with the AfD and its electorate, the open society need not be undermined. Since 13% of the German electorate voted for the AfD it is important that its grievances are publicly discussed rather than merely discarded. It will be up to the other parties, the media, and the public to safeguard the open society and ensure the AfD does not “poison the content of Germany’s political discourse” by consistently challenging the AfD’s discourse and that of those who replicate it.

This article is the first in a series of articles about the meaning(s) of the open society in Europe, published as part of d|part and OSEPI’s joint action-research project “Voices on Values”.

–

The authors, Magali Mohr and Dr. Luuk Molthof, are Senior Research Fellows at d|part and conduct research for the Voices on Values project.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors.

–

[1] See for instance Mark Beise and Hans-Jochen Vogel.

[2] See for instance the comments by Daniel Erk, Elmar Theveßen, and Matthias Matthijs & Erik Jones.

[3] For instance, the PVV received 13,1% in the last Dutch parliamentary elections, the DF 21,1% in the last Danish parliamentary elections, and the FPÖ 26% in the last Austrian parliamentary elections.

[4] See SPD — ‘Zeit für mehr Gerechtigkeit’; CDU — ‘Für ein Deutschland in dem wir gut und gerne leben’; FDP — ‘Denken wir neu’; Die Linke — ‘Sozial. Gerecht. Frieden. Für alle — Die Zukunft, für die wir kämpfen!’; Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen — ‘Zukunft wird aus Mut gemacht’.