(Un-)democratic populism and new parties in Europe

by Anne Heyer.

Prelude to the blog series: The new populist parties in Europe?

Europe’s new spectre

A spectre is haunting Europe. No, this time around it is not Marx’ old tale of the Communist Party that haunted Europe’s then brand new nation states. This time, it is a whole range of new political parties that unsettle Europe’s by now pretty established democracies.

For a few decades already, these new parties – populist ones – have not only upset the political establishment; they are significantly changing Europe’s political landscape. Starting from France’s Front National, the Austrian FPÖ and Belgium’s Vlaams Blok, we can continue the list calling out the Danish Progress Party or the Sweden Democrats until we reach Poland’s Law & Justice Party (PiS) or the Hungarian Fides. All of these illustrate a phenomenon of (re-)emerging right-wing populism.

In the context of this spectacle some political scientists have argued that these new parties are inspired by a common European narrative: one that aims to give a voice to all those who are not united by the postmodern values of leftist social movements.[1] However, there are also rising stars on the left side of the political party horizon, such as Syriza in Greece or Podemos in Spain. Even Germany, a country that – for obvious historical reasons — has been immune to the rise of a new populist party for a long time, has acquired a new political actor right of centre. The Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) does not only feature a populist tone; it is also positioned on the political right, in fact, even right of both of the traditional conservative parties of Christian Democracy, CDU and CSU.

A series of blog posts: Europe’s new populist parties

Many of these very different populist parties have become quite successful in the way they influence political debates and put pressure on established political actors. However, we can also find more nuanced accounts of their recent wave of success. So what is the matter really with this new populist spectre haunting Europe? Some seem to believe that this phenomenon poses a serious threat to representative democracy. Others proclaim the opposite: the rise of a new era of direct or deliberative democracy. These divergent positions make it difficult — albeit all the more necessary! – to give a differentiated account of what to make of these new populist parties, both in the national as well as in the broader European context.

In the coming months, we will tackle exactly this challenge: here at our blog we will take a good look at the phenomenon of new populist parties. We will do so from various different angles: we will present local experts‘ analyses of and opinions on some of these rising populist parties individually, but also in comparison with each other when viewed in the broader European context. The aim of all of this is to give a balanced account of an issue that is highly topical across Europe. Based on deep dives into opinions on different new populist parties, we aim to provide a range of perspectives on what could be a pan-European phenomenon. Taken together, the contributions in this series of blog posts will offer unique insights into the various perspectives on this complex phenomenon of new populist parties. Even if some analysts have already claimed to observe parallels between the various new parties in different parts of Europe, we think it is worthwhile to take an even closer look in order to identify both similarities and differences.

Talking to the people in the street

Aiming to provide an alternative to the often one-sided coverage that these new parties receive these days, our compilation of blog posts will offer a differentiated survey. Especially all those who have come into office through long-established political parties seem to have little nuanced to say about this new phenomenon. When asked about the rise of these new populist parties, established party politicians have often criticized them as viciously captivating innocent voters with populist rhetoric, much like Pied Piper of Hamelin who lured innocent children out of town with his magic pipe. Consequently, in this narrative the members of such new populist parties are not individuals who think and act independently, but rather are characterized as weak and “susceptible to this new populism”.

In this context, the term “populist” always bears a pejorative connotation. This is quite surprising considering that populism originates from the Latin word “populus”, which simply refers to the people. Even among the most creative accounts of democracy, the people are still considered to be democracy’s main source of legitimacy. By the way, democracy derives from the Greek word “demos” which – surprise, surprise! – also refers to the people. If we wanted to provoke an argument here, we could even say that the leaders of these new populist parties, UKIP’s Nigel Farage or Syriza’s Alexis Tsipras, are doing exactly what they should be doing according to the definition of democracy: talking to the people in the street. This idiom reportedly goes back to the father figure of all Protestants — Martin Luther.

What exactly is populism? Is it dangerous?

So is there any point at all in distinguishing the new populist parties from old, long-established ones? First of all, there is obviously a difference in chronology: historically the “old” parties were established before the “new” parties. However, some of these “new” parties are more than four decades old. France’s Front National, for example, celebrates its 40th anniversary this year.

In addition to chronology, these new parties seem to differ from established ones in their form and in the content they raise. In an effort to bring the people closer to the politics, and the other way around, they often fare radical demands for simple political solutions that involve emotions and elements of direct democracy. For those new populist parties that find their place right of centre, there is also a notable shift towards a notion of the community built on shared values and culture (as opposed to previous and outdated notions of an ethnic community).[2] Assuming that the representation of pluralistic interests is one of the pillars of democracy, this claim of cultural uniqueness poses a serious threat, not only to the political elites but also to us, the general public!

Possible similarities of new populist parties

- Positioned as true representatives of the people as opposed to the political (often corrupt) elites or other established actors

- Demand simple solutions to complex problems

- Mistrust or even oppose the EU as a political project

Nonetheless, we have to ask the question whether populism in itself is a problem for democratic societies. Many established parties also resort to populist rhetoric – and I am not only referring to Germany’s omnipresent Horst Seehofer, head of the Bavarian branch of the ruling Christian Democrats, who himself claims to have a soft spot for populist statements. Other high-ranking politicians who have uttered “clear statements” in “plain language” – arguably containing a certain populist element – can be found in any European democracy: an illustration is this collection of quotes by Germany’s vice chancellor Sigmar Gabriel or – my personal favourite – a rare breed of genetically modified peppers who had their coming out in Austria’s 2015 election campaign of the Green Party.

In the context of the rising Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), for example, a number of analysts have debated the question in how far established parties are doing anything different from what this allegedly new populist party is doing (e.g. die Zeit and der Spiegel). Interestingly, the early democratic parties of the 19th century also advertised with slogans addressing the people as opposed to the political elites. And it is probably not coincidental that the slogan that peacefully toppled the GDR in 1989 was that of “We Are the People”. As a consequence, according to a number of political scientists, populism can be seen as an important pillar of democracy.[3] It is addressing the emotional side of our minds, in contrast to the rational side that considers facts and works towards compromise. In this light, we could even argue that the phenomenon of new populist parties is giving established democracies a sort of epiphany: that walking only works on two legs!

All quiet on the Southern front?

This perspective is reinforced when we look at what is happening in Southern Europe: Greece’s Syriza or Spain’s Podemos illustrate that the phenomenon of new populist parties is, in fact, not necessarily limited to only right-wing politics. Elements of populism are also discernible left-of-centre. Can we compare these left-wing populists with their stepbrothers on the right hand of the political spectrum? Intuitively, we have to ask the question what it is exactly that these new parties – whether right or left of centre – have in common. What else do they share, besides the observation that they all are fairly new kids on the block? And – to put it straight – is it justifiable to claim that all of these left- or right-wing populist parties are part of the same phenomenon? Or do we rather have to evaluate them independently, each party in its own national context?

One feature that all new populist parties in Europe have in common is their distrust of and opposition to the influence of the EU on national politics. A negative image of Brussels is what unifies these new parties across Europe, left and right of centre. For many of them, this opposition towards European integration also played a key role in their founding narratives. At this point we can thus conclude that there are at least some similarities and differences that deserve a closer analysis.

Possible differences between new populist parties

- Organisational structure

- Founding history, circumstances and time

- Position on the political left-right spectrum

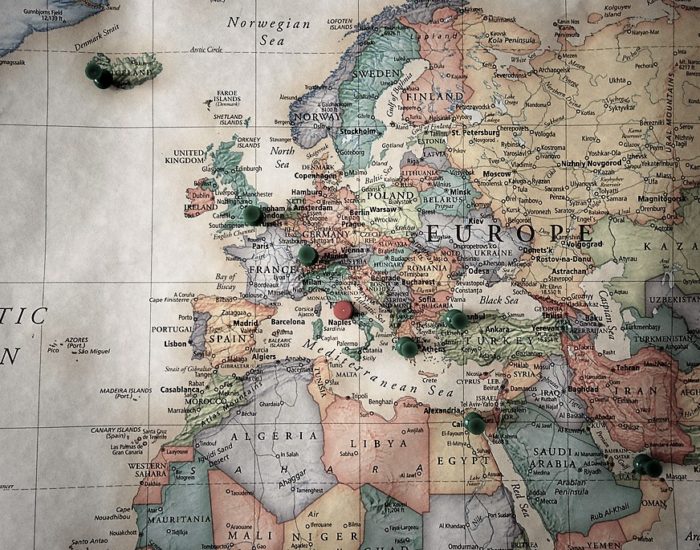

For the coming months, we have a whole series of blog posts in store for you that will build on these first insights. Roughly on a monthly basis, we will publish contributions of various local experts, who will provide their views on new populist parties and what they could have in common with their European counterparts (if anything at all). Our contributors take us on a roadtrip all across Europe from its Southern border, where Greece’s Syriza deserves attention, to the East, where the Polish PiS made its way into government, and all the way to the Northwest, where Britain’s UKIP is an infamous addition to the political landscape. It is local experts who will provide unique insights and allow us to see the bigger picture of a European development (or not). Even if the length of these posts will probably not increase proportionate to the length of daylight, I promise an exciting spring on this blog.

It seems that the biosphere of European democracies is changing for good. This series of blog posts will introduce a new species of political parties to you that you should not miss to learn about. We will first turn to the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) before we move on to Poland’s PiS and Greece’s Syriza. Stay tuned, check this blog again in a couple of weeks or follow us on Twitter or Facebook to find out what these new populist parties have in common and which other parties we will compare.

–

Anne Heyer is an Affiliate at d|part.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

–

[1] P. Ignazi, “The Crisis of Parties and the Rise of New Political Parties,” Party Politics2, no. 4 (October 1, 1996): 549–66.

[2] Jens Rydgren, “Is Extreme Right-Wing Populism Contagious? Explaining the Emergence of a New Party Family,” European Journal of Political Research 44, no. 3 (2005): 413–37.

[3] Margaret Canovan, “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy,”Political Studies 47, no. 1 (March 1999): 2.

–

Picture: ‘L’uomo con il megafono — The man with the megaphone’ courtesy of Angolo Bianco, released under Creative Commons.