When elections are a crisis – because the market tells us so: The case of Greece

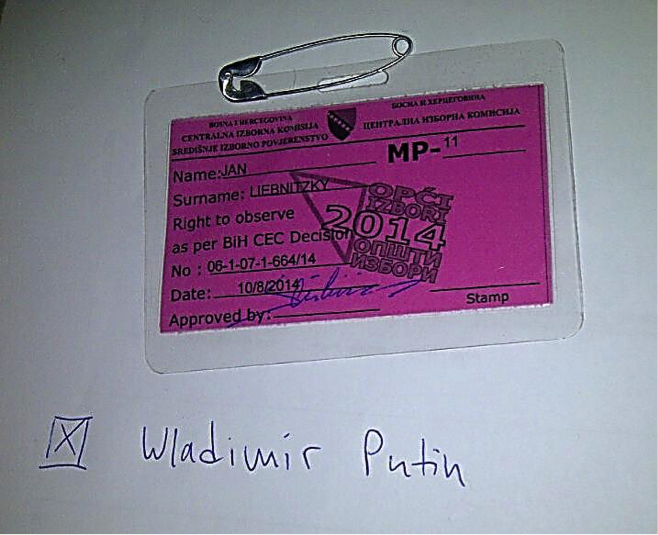

By Jan Eichhorn.

Over the past week I found myself rather dumbfounded on multiple occasions. Reading newspapers from Germany, the UK and the USA I kept finding headlines that suggested Greece was in crisis – a massive crisis with huge consequences for Greece itself and the Eurozone overall.

Now, I agree with that of course. Greece is in crisis indeed. Unemployment remains incredibly high, industrial activity has diminished in unprecedented levels, emigration increased meaning that in particular bright people leave the country to find opportunities elsewhere and there is no real sign of a great improvement for the lives of the majority of the people who have been hit so hard by the austerity measures of the past years. But that was not what most of the media outlets I read referred to.

They had painted a different picture of Greece in recent months. As recently as November 2014, we could see titles such as “Greece Returns to Growth”[1] from a variety of analysts. That this was small growth on the basis of a strongly contracted economy was less frequently mentioned. Also, that it did not mean tangible improvements in living standards for most crisis-affected Greeks often stayed out of the picture. The crisis was under control and the worst over in the eyes of many commentators who seem to mistake simple indices for actual measures of real circumstances.

But now we have a crisis again. Why? Greece has an election. The government-favoured candidate for the presidency did not receive the required number of votes and according to the Greek constitution that requires the election of a new parliament. To me that does not meet the definition of crisis, in particular not a political crisis – as many claimed this would be. The reason is simple: All that is happening is that a normal constitutional process is being run. That would imply that any time in any country where a parliament did not see through its full term and earlier elections were held, completely in congruence with the rules stipulated by the country’s respective constitution, we would have a political crisis at hand in that country. We’d live in a world of political crisis inflation in that case.

The problem of course is a different one. This time polls suggest that the left-wing party Syriza may win the elections. They oppose the current direction of the contractionary, austerity based policy for Greece. There is nothing wrong with discussing the economic and political consequences of what changes to current decisions would imply. But if the Greek people voted for this direction in a democratically legitimate election, then labelling this a political crisis is simply wrong at best and undemocratic at worst. It would imply that the sovereign will of a people is only legitimate when it matches the preferences of the elected parliaments and governments of other states – and that of opinion makers in the markets and media outlets.

The label crisis is paternalistic and arrogant at this point in time. The situation is not adequately reflected by headlines such as “Greece plunged into crisis as failure to elect president sets up snap election”.[2] Of course, there are possibilities of further crises following any changes. But right now, the existing main crisis in Greece is that of a decimated economy and massively reduced living standards for the majority of people. What we see in Greece this week simply is not a political crisis. It is democracy.

What has happened of course is that markets, in particular bond and stock markets reacted to this. Their negative reaction in anticipation of possible, currently only hypothesised election results, following policy decisions and subsequent results, is seen as the marker of crisis. And while in many countries we are made to believe that this is because there is only one possible response to the crisis (i.e. austerity policies, the effectiveness of which is highly questionable — but that would go too far to discuss here), and that we ought to be very concerned about this political “crisis” in Greece, we should be a bit more critical. What the actual interests by market actors are might be better summarised by comment pieces such as “The stocks to buy if the Greek crisis hits U.S. markets” from 5 January 2015.[3]

If the Greek people decide to define what they have right now as crisis and vote for alternative policies hoping to better their situation it is the most normal democratic process imaginable. If we want to debate the consequences for certain markets, country budgets and the Euro as a currency, that is fine, too. But what is utterly inappropriate is to use a particular preference of how things should develop in our interests in other places to frame constitutionally legitimate processes and sovereign decisions of the Greek people as a political crisis thus trying to delegitimise their decision.

[1] http://www.nasdaq.com/article/greece-returns-to-growth-20141128–00082

[2] http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/29/greece-crisis-president-snap-election

[3] http://blogs.marketwatch.com/cody/2015/01/05/the-stocks-to-buy-if-the-greek-crisis-hits-u-s-markets/

–

The author of this article, Dr Jan Eichhorn, is the research director of d|part and oversees the work on the Voices on Values project. He also teaches Social Policy at the University of Edinburgh.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.